Re-Emergence of Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs) − Current Challenges & Threats

#rethinkcompliance Blog | Post from 23.08.2022

The Beginning of an End?

The fundamental concept of “foreign fighters” is not a modern-day innovation; historically, fighters from abroad have participated in several civil wars. A classic example is the International Brigades, a militant group constituted of foreign fighter volunteers from 50 different countries participating in Spanish Civil War. In the present time, however, the definition of foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs) has gained in importance after its adoption in the Security Council Resolution 2170 (2014) following the Iraq crisis, which has been reaffirmed in the UNSC Res. 2396 (2017). A recently published joint report by Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG) and Global Center on Cooperative Security attempted to explore the nuances of behavioural and financial profiles of FTFs in Southeast Asia by gathering and utilising financial intelligence by the Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs) across this region to analyse and combat the catalytic effect of FTFs on terrorist activities.

The death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of ISIS in 2019, led to the immediate appointment of Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi as the following leader of the Islamic State.[1] He was an ex-Iraqi army official, who had served Saddam Hussein, as well as a policymaker and was killed in a US raid in northern Syria earlier this year.[2] Also, he was placed on OFAC’s Specially Designated Global Terrorist list raising the question: Is this really the beginning of the end of violent terrorism perpetrated by one of the most powerful extremist organisations in modern history? Maybe not. Given the diminishing importance and influence of IS in recent years, several pro-ISIS offshoots are beginning to regroup with the hope to revive IS with any means available, including the recruitment of FTFs and the reception and utilisation of their returnees in their respective home countries. These offshoot organisations include multiple militant groups in Southeast Asia, such as Tawhid-wal Jihad, Katibah Nusantara (a group responsible for 2016 Jakarta Terrorist attacks), the Maute Group, FAKSI (a group from Java, Indonesisa pledging allegiance to ISIS) and many more. There already is a growing concern of FTFs being recruited via social media by several ISIS affiliates, sympathisers, and returnees from the Asian Pacific area.[3]

This article evaluates the threats posed by FTFs and the systems currently deployed to identify and assess the tactical and evasive methods used by foreign fighters.[4] Moreover, this article attempts to understand the movement, financial profile and transaction patterns and the potential red flags leading to the detection and prosecution. Finally, the article aims to serve as an additional source of knowledge on FTF profiling for compliance officers, anti-money laundering practitioners, and financial analysts in the counterterrorism landscape.

Who are the Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs)?

In order to respond effectively and efficiently to imminent re-emerging terrorist threats, it is imperative not only to identify the mechanisms of FTF transactional and behavioural patterns, the geographical emanation, transit and destination hubs as well as FTF returnees, but also to comprehend the FTF definition as described in the UNSC resolutions 1373 (2001), 2462 (2019), and 2178 (2014).

According to the UNSC resolution 2178,

“foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs) are those individuals who travel or attempt to travel to a State other than their States of residence or nationality, and other individuals who travel or attempt to travel from their territories to a State other than their States of residence or nationality, for the purpose of the perpetration, planning, or preparation of, or participation in, terrorist acts, or the providing or receiving of terrorist training , including in connection with armed conflict.”[5]

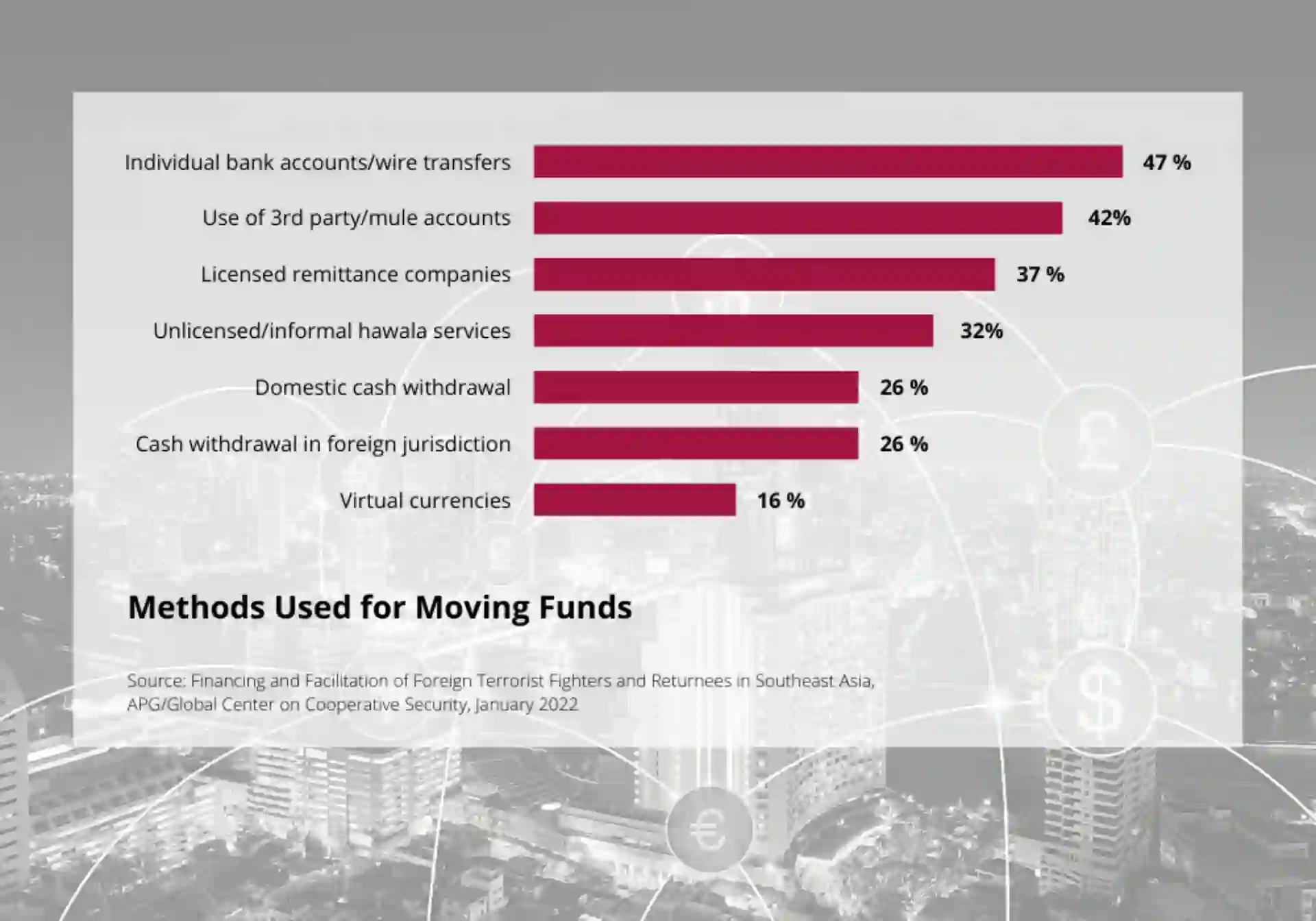

FTF planning, preparation and deployment require funds, so it is important to understand the geographical footprint and phases of FTF movements. This includes the point of origin, the transit routes and the various means of funding used to enable FTFs to carry out terrorist activities at the designated spots. Below snippet highlights commonly used methods for movement of funds involving FTFs.

Surveys of APG members including law enforcement and intelligence agencies have revealed that typically licensed and unlicensed remittance companies, wire transfers and cash withdrawals at home and abroad have been extensively utilised by the foreign fighters and their recruiting agents.

Re-Emergence & Drivers of FTF Activities

Part of the reason why ISIL offshoots are targeting Southeast Asia for recruitment is the influence of ISIS extremists on new militants, who view the group as the true bearer of the jihadi principles they have long upheld. Another factor for FTF re-emergence in the Southeast out of Daesh/ISIS is the affirmative influence of former members’ biased accounts on new militants, whose motivations are a complex mix of social, economic, cultural, ideological, and personal reasons. However, the following inexhaustive list sums up the main motivational factors for FTFs.[6]

- Religious narratives within the eschatologically oriented and misguided people willing to live under the rule of the so-called caliphate

- Ideological conviction

- Desire to improve the poor political and humanitarian conditions attributed to the atrocities of Syrian Civil War and oppressive dictatorship in Syria (typically a conflict-ridden zone in a broader sense)

- Sense of belonging, adventure, respect, opportunities for economic advancement, employment, marriage, and other material benefits

Following the territorial collapse of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant in particular, FTF recruitment focuses its attention on individuals and their families that are detained in camps, returning to their countries of origin, or travelling to a third country as well as on children of foreign fighters. However, several states have revoked FTFs’ citizenships to prevent their return, rendering them stateless.

Usage of Financial Intelligence against FTFs

In addition to a more generalised approach for the identification of red flag indicators aimed towards terrorist activities, more detailed information could benefit private sector actors in detecting and disrupting suspicious transactions related to FTFs or terrorist financing activities.

Example: Information about a very specific geographical area that is alleged to be a terrorist hotspot will enable reporting entities in the future to both better manage their risk of exposure to terrorist financing as well as to report more actionable and useful financial intelligence.

Below illustration shows a typical pattern of movement of foreign fighters which is subdivided into four to five stages.

Prior to Departure

- Pre-planned cessation of account activity by FTF

- Account statements indicating sale of personal possessions prior to date of travel

- Airline ticket purchases in proximity to conflict zones

- Account activity indicating funds received from social assistance, student loans, or other credit products

- Donations to NPOs linked to terrorist financing activities

- Use of funds for other travel-related items

En Route

- Irrational circuit of travel routes to the conflict zone with multiple means of travel

- Notice about a travel to a third country via a conflict zone but financial activities indicating an incomplete journey

- Financial activity alongside corridor to a conflict zone

- Receipt of wires inside or along the border of a conflict zone

In Theatre

- Inward money transfers from friends and relatives or terrorist accomplices

- Account goes dormant

- Media coverage on individual travellers to conflict zones

Return

- Dormant account suddenly becomes active

- Receiving new sources of income

- Atypical domestic or international fund transfers

Current Challenges

The categorisation as FTF depends on domestic legislation, which is guided by the international standard definition of whether the suspected individuals are “FTFs” or the groups they join are “designated terrorist groups”. This can cause inconsistencies in the application of FTF terminology, which is why it is imperative to adopt a globally accepted standard definition that makes a distinction between the terminologies of FTFs, general terrorists and the ones related to an armed conflict.

Additionally, the current red flag indicators for FTFs are rather broad and heavily biased toward the geographic location of the transactions associated with travel to a conflict zone or border region without the ability to determine whether they are legitimate or illegitimate. Lack of such information as well as the common profile of FTFs remain a practical challenge not only for the definition and identification of FTFs, but also for the analysis of their financial, behavioural, and geographic movement.

The usage of cash transactions between unknown, unrelated individuals and the transnational nature of FTF transactions constitute additional challenges. As customs and border officials are the first line of defence in the fight against FTFs, including them in the policy framework could be beneficial for an effective identification of FTFs and an appropriate reaction to FTF activities.

Another challenge is the lack of a robust feedback channel: Transactional relationships between law enforcement agencies (LEAs) and financial institutes (FIs) lack feedback on the quality and usefulness of information, which remains a bottleneck for investigating agencies in their collaborative efforts against foreign terrorists. Domestic communication from the financial and private sector and FIUs to law enforcement agencies is a one-way channel.[7] Feedback on a broad basis is important, not only in relation to specific cases. This is crucial to validate the correct flagging of information and how to improve reporting. This will help FIUs improve the refining of indicators, the quality and reliability of STRs as well as strategic and actionable intelligence.

Conclusion

While some APG members are continuously working on developing regulatory frameworks and strengthening their domestic AML CFT policies and procedures to prevent FTF activities and terrorism as a whole, other states have yet to establish (and, where already in place, reinforce) a well-defined AML framework to combat the financing of terrorism and intercept terrorist activities.

Governments also need to be mindful about the blurred lines of distinction between human rights violations, the categorisation of FTFs and armed conflicts versus a generalisation of terrorism. While several legal and compliance practitioners, FIUs and LEAs have investigated FTF related cases and developed a preliminary basis of red flags and indicators for the identification of FTFs, there still remain practical challenges to explicitly identify FTFs. At the moment, little data is available on incarcerated FTFs, as much of the information provided is unreliable and biased.

However, a combination of factors such as social and behavioural profiling of FTFs, geolocation and travel pattern analysis, understanding irrational account activity and a robust feedback communication between LEAs and FIUs will contribute to the preparedness against FTFs destabilising the region.

[1]Islamic State group names its new leader as Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi - BBC News

[2]Islamic State leader Abu Ibrahim al-Qurayshi killed in Syria, US says - BBC News

[3]Southeast Asian Analysts: IS Steps Up Recruitment in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines

[4]Publication of Financing and Facilitation of FTFs and Returnees in Southeast Asia Report

[5]Investigation, Prosecution and Adjudication of Foreign Terrorist Fighter Cases for South and South-East Asia (unodc.org)

[6]Foreign Terrorist Fighters - Manual for Judicial Training Institutes South-Eastern Europe

[7]Publication of Financing and Facilitation of FTFs and Returnees in Southeast Asia Report

Author

Ritwij Jain

Financial Crime Compliance (FCC) Business Advisory Expert | 10+ Years of Experience as Consultant and Compliance Specialist at a Leading AFC Compliance Solutions Provider and at Several Global Banks | Techno-Functional Consulting across the APAC Region